Urban poor increasingly made homeless in India’s drive for more ‘beautiful’ cities By Dunu Roy, Combat Law

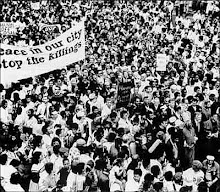

16 January 2005: When Mumbai (Bombay) Municipal Corporation evicted pavement dwellers in 1981, a journalist came forward to file a public interest petition to protect the rights of the pavement dwellers. After five years in 1986, the case became a landmark judgment that maintained that the Right to Life included the Right to Livelihood. As livelihood of the poor depends directly on where they live, this was a verdict in favour of pavement dwellers.In the early 70s the city passed Slum Clearance Act, while the Slum Upgradation Scheme was conceptualised in the 80s, which later became the Slum Redevelopment Scheme of the 90s. But at the turn of the century the very same metropolis used massive force with helicopters and armed police, to evict 73,000 families from the periphery of the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. This action was in response to Court orders in another ‘public interest’ petition, but filed this time by the Bombay Environmental Action Group (BEAG). What the BEAG appeared to be concerned about was the protection of a 28-square kilometre ‘National’ Park, particularly the one-third reserved for ‘tourism’. But no one seemed to be bothered by either the sundry religious Ashrams inside the Park or the proliferating blocks of private apartment houses on its boundary. What, then, was common to the nature of "public interest" espoused by Tellis and the BEAG, and how did the Court view either or both? And were there any radical social changes in the twenty years that intervened between the two?Urban developmentIn Chennai City 40 per cent of the population lives in slums - there are 69,000 families who have been identified to be living on government land and they are to be relocated to areas far removed from the city. The areas vacated will be taken over by railway tracks, hotel resorts, commercial and residential complexes, and modern businesses. Much of the ‘clearance’ is being undertaken in the name of ‘beautification’ and tourism.In Kolkata (Calcutta) the Left Front government though claims to be pro-poor also is working on ‘environmental improvement’ projects. Operation Sunshine was launched in 1996 to evict over 50,000 hawkers from the city's main streets. Currently over 7,000 hutments are being forcibly demolished along the sides of storm water drains and the metro and circular rail tracks. At the same time, lavish commercial and residential complexes are coming up unhindered along the metropolitan bypass, where the real estate prices rival those in the elite areas of South Calcutta.Delhi, where sub-standard settlements house as much as 70 per cent of the city's population, leads the way in environmental activism. Not only have vendors, cycle-rickshaws, beggars, shanties, polluting and non-conforming industries, and diesel buses already been ‘evicted’, A recent addition to the hit list are the 75,000 families who live on the banks of the Yamuna river. They are being held responsible for the river's pollution.In 1997, Hyderabad was distributing land titles and housing loans to the urban poor, but during the TDP tenure the state had leased large areas of land at heavily subsidized rate to business groups, international airports, cinemas, shopping complexes, hotels, corporate hospitals, and railway tracks. Over 10,000 houses of the ‘weaker members of society’ have been demolished to make way for the new face of ‘Cyber bad’.Urban planning trendsLarge areas of habitation of India’s urban poor have been forcefully taken over by every government - regardless of political make-up. The groups of people affected are often the ones who have been employed in informal sectors or are self-employed in the tertiary services sector. Their displacement is much to do with the space they live in as with the work they perform.The areas that they occupied are being transferred into larger private corporate entities such as commercial complexes and residential developments. These units are also often coupled with labour-replacing devices ranging from automatic tellers and computer-aided machines to vacuum cleaners and home delivery services, thus eliminating the work earlier done by the lower rungs of the urban population.While the driving force behind these changes is manifestly the new globalised economy, it is offered on an environmental platter of ‘cleanliness’ and ‘beautification’.In vicious combination these three trends are changing the urban landscape from ‘homes’ to ‘estate ownerships’ in the name of liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation. Concepts of urban planning too are changing in harmony with these trends although, as we shall see later, the seeds were sown long ago as capitalist empire spread its hegemony over the world.The replacement of housing of poor urban dwellers with commercial and upmarket developments raises several questions about the nature of ‘planning’ itself. Who makes these plans? Who are they made for? Do the planners take into account actual data from the study of how cities grow?Urban planning in DelhiThe Delhi Development Authority (DDA) was constituted in 1957 to check the haphazard and unplanned growth of Delhi... with its sprawling residential colonies, without proper layouts and without the conveniences of life, and to promote and secure the development of Delhi according to plan". For the three years the DDA guided by experts from the Ford Foundation had developed a Master Plan for Delhi for 20 years and this was presented along with maps and charts for unprecedented ‘public’ discussion in 1960. The public debate on this initial document elicited over 600 objections and suggestions from ‘the public, cooperative house-building societies, associations of industrialists, local bodies, and various Ministries and Departments of the Government of India’. An ad-hoc Board was appointed to go into all these objections and it gave its recommendations to the DDA in 1961.Eventually the Master Plan of Delhi was formally sanctioned in 1962. Predictably, the first concern of this Plan was the growth in the urban population and the planners proposed to restrict it by building a 1.6 km wide green belt around the city and diverting the surplus population to the adjacent ‘ring towns’. It was also decided that the ‘congested’ population of the walled city would be relocated in New Delhi and Civil Lines. At the same time several new industrial and commercial areas were declared for promoting growth. Thus, the DDA saw merit in both earning more revenue through industrial expansion as well as reducing expenses by curbing population increase, without examining the necessary linkage between the two.Delhi's expansionBut it was in 1971 that it became clear that the city's growth is far beyond the conception of planners. The total number of industries had increased to 26,000 and there was a huge spurt in the squatter and ‘unauthorized’ settlements. So, in a frantic burst of activity to ‘restore order’, the administrative machinery swung into action and from 1975 to 1977 1.5 Lakh (one lakh = 100,000) squatter families were forcibly moved out of the city into resettlement colonies on the periphery. Each family was entitled to a plot of only 25 square yards with common services and 60,000 such plots were demarcated on the low-lying Yamuna flood plain alone. Interestingly enough, all the resettlements were located very near the new industrial and residential areas, presumably designed to provide cheap and docile labour. This labour force was further enlarged by another 10 lakhs in 1982 when the Asian Games overtook the city. Numerous stadiums, shops, roads, hotels, flyovers, offices, apartments, and colonies were constructed to cater to the needs of the Games and the anticipated commercial spillover. The second Ring Road became a magnet for further commercial and residential development. But the city could not cope with this additional burden.In 1985, the National Capital Region Board was set up to plan for a balanced growth of extended region around the capital. Also in 1985, the second master plan draft was published for comments. However, unlike the first plan, this one was not summarized or translated into Hindi and Urdu, nor it was distributed publicly. Nevertheless, the draft came in for severe criticism from the government itself as being ‘conceptually defective’ and the Delhi Urban Arts Commission (DUAC) was asked to prepare another plan. The DUAC took a close look at the failures of the first master plan to detail its own conceptual plan. But their plan was also rejected by DDA and there was no public hearing, but the draft was discussed in the select committee. In order to avoid public consultation and parliamentary debate, it was decided that the second plan would only be ‘precisely a comprehensive revision of the first one’.This revised version identified that major part of the city's problems originated outside and their solutions lay beyond its territory. It too recommended for de-industrialization, maintenance of ecological balance in the Ridge and the Yamuna, decentralisation into districts, and provision of multi-nodal mass transport, with low-rise high-density urbanization. Interestingly enough, it called for a special area status for the walled city as "it cannot be developed on the basis of normal planning policies and controls". In fact the planners did not even understand the implications of what they themselves had done. For example in 1988 during the cholera outbreak 1500 people died in the 44 resettlement colonies they had planned in 1975. It was recognized that the disease had spread through ground water contamination by inadequate sanitation measures in the low-lying areas but an embarrassed administration shied away from being held responsible. Thus, the new plan not only failed in tackling the problems, but also they did not even incorporate their own analysis of failures and weaknesses of past planning into its recommendations.As the date for yet another Master Plan approaches, this systemic failure of modern planning is evident in the situation as it obtains today. Delhi has spread far beyond the confines of the Outer Ring Road. The original green belt has largely fallen victim to land developers, including the DDA itself. The resettlement colonies and industrial areas, that were once supposed to be at the fringe of the city, have been drawn into its ambit. The ring towns are now contiguous urban sprawls and the arterial roads and national highways are the most congested in the region. Increasing numbers of poor inhabitants continue to live in shantytowns without services. It is presently estimated that around 60 percent of the population live in sub-standard housing. Rapidly shrinking employment opportunities and crusading environmental activism have made the situation significantly worse for them. While the city gets the Clean City Award from far-off California, it's own citizens grimly face critical inadequacies of work, shelter, civic amenities and governance.The guidelines for the new plan issued by the Ministry of Urban Development refuse to address these issues. Instead they focus on how to promote private participation and market competition in land, housing, and services; how to protect heritage, encourage tourism, and increase revenues; and how to obey the twin dictates of military order and profitable commerce. The fact is that the planners have not learnt any lessons from past disasters, such as the jaundice and cholera epidemics and the Asian Games. The jubilant and manipulated voices that accompany the announcement of the Yamuna canalisation plans and the gigantic mall on the Ridge and the looming Commonwealth Games testifies to the total bankruptcy and arrogance of the overall city planning process.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment