The Community Development Students of Rajagiri College Of Social Sciences has organized a Chaakkiyaar Koothu on 08- 02- 2010 at 2 pm in the College Auditorium. The main objective behind this effort was to make the young generation aware of the rich cultural heritage our Keralam possesses. Chaakkiyaar Koothu has been losing its importance with the increased impact of the modern media on the minds of the youth. Rajagirians honoured the blessed artist of the present times... Mr. Pothiyil Narayanan and arranged a venue to popularize the event.

The participation was beyond expectation and the hall was filled with 100's of viewers. The students and the faculty members had a great evening!!!

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

Friday, February 5, 2010

WASTE WATCH

What is Waste and Why is it a Problem?

Wastes are variety of materials that are no longer required by people. We usually call this garbage. Waste is a natural by-product of any process on Earth and cannot be avoided. Nature reuses all of its by-products, with no waste in the end. What is waste for one is useful for another. For example dead leaves decompose to provide nutrients to plants and oxygen released from trees is used by us.

We humans, however, have disturbed this balance by bringing in new problems such as toxic and non-degradable wastes and even nuclear wastes into the environment. Even ‘normal’ solid waste is now a problem because there is too much of it. Studies show that on an average, each person in urban areas produces half a kilogram of garbage each day. This doesn’t include the garbage we make indirectly - through industry, agriculture and mining. Twenty per cent of Indians live in urban areas. This calculates to more than 36 million tons of garbage each year in cities alone !

Though waste generated has increased, the way we deal with the disposal of waste has not changed in over ten thousand years. We pile it and then burn it, or bury it in some out-of-the-way place where we forget about it. But today, we are faced with too much garbage and not enough places left to throw it away. Improper disposal of solid wastes has lead to ground water contamination, air pollution, health hazards etc.

CLEAN-India Helps Manage Waste Better

The members of CLEAN programme are made aware of the glaring (but overlooked) problem of waste in our cities. Activities and film shows have made students aware of the solid waste problem in urban areas and their role in reducing it. Issues like the ill effects of polybags, littering on our streets, excessive consumerism are all discussed and deliberated with student groups. Clean-up drives in local parks and markets are organised in which students very enthusiastically help in cleaning up and drive home the message that adults should not indulge in littering.

With the objective of managing the waste locally through simple techniques, natural composting, vermicomposting, paper recycling and Reuse Society have been initiated in schools and community.

Composting

Composting is, in the broadest terms, the biological reduction of organic wastes to humus. Whenever a plant / animal dies, its remains are attacked by soil micro-organisms and are reduced to an earthlike substance that is beneficial for the growth of plant (roots). This process is repeated universally and continuously in every part of the world, and is a part of the wheel of life.

Two methods of Composting undertaken at the school level are Vermicomposting and Natural Composting.

Natural Composting

In natural composting, the waste decomposes with the aid of other factors such as insects, worms and tiny microbes. This is possible in each and every school, irrespective of the amount of waste they generate. Schools that do not have their own canteens and consequently have little biodegradable waste generated can adopt this project. They can decompose all their garden waste easily by alternatively layering a pit ( 1 m deep, 1 m wide and 1 m.long, as per convenience) with the waste and soil. This form of composting is recommended particularly for those schools which have a lot of garden waste like dried leaves that can be saved from burning. The compost thus generated is used in the school lawns and gardens as a substitute for manure, thus saving the cost of fertilisers.

Vermicomposting

This is the process through which we can convert biodegradable waste into rich humus by using earthworms. After an earthworm ingests organic matter, the matter undergoes chemical changes and what comes out is a rich plant food. This makes our soil fertile and plants stronger. Then we need not buy chemical fertilisers.

Many CLEAN-India schools, that have their own canteens and gardens have adopted this project. Hands-on-experience in vermicomposting shows students effective ways of taking care of biodegradable waste. The project not only solves the problem of solid waste to an extent and gives rich compost in return, it also helps students realize the importance of small creatures like earthworms and helps them shed their fear. In the process it brings alive the concepts learnt in class about decomposition in nature and how earthworms function. In many schools, the compost produced is also sold to the parents. Few schools like Shri Ram and Joseph and Mary in Delhi are now providing earthworms and helping people of nearby villages to initiate their own vermicomposting units.

Re-Use Society

A king once offered five hundred garments to a disciple of Buddha.The king asked the disciple what he would do with so many garments ?The Disciple replied : " Oh King, many of our brothers are in rags:I am going to distribute the garments among brothers."What will you do with the old garments ?We will make bed - covers out of them.What will you do with the old bed - covers ?We will make pillow - cases out of them.What will you do with the old pillow - cases ?We will make floor - covers out of them.What will you do with the old floor - covers ?We will use them for foot towels .What will you do with the old foot - towels ?Your highness, we will tear them into pieces,mix them with mud and use the mud to plaster the house walls.

What is waste for you, is wealth for somebody else. There has been a tradition in India of finding an innovative use for every thing: - tyres, battery cases, plastic bins and what not. A similar thing is started in School which saves both the environment and money in the bargain, in addition to inculcating in students a habit of not discarding things unthinkingly.

Apart from making innovative things from discarded things in the Crafts Period, two major activities are suggested to the school under the Reuse Society. The first activity is to exchange books and even notes at the beginning of each academic session. Students of a senior class give the books to the students of a junior class and, in turn, receive books from the senior section, and a chain is established throughout the school. This way a lot of paper and consequently trees can be saved.

The next major activity in the Reuse Society is to donate books and outgrown clothes, toys, etc. The books / story books /comics that have been read and re-read, the clothes and shoes that have outgrown, are collected in schools and given to the less fortunate children of the society. Such collection is presented to Child Welfare organizations, slums, orphanages etc.

Wastes are variety of materials that are no longer required by people. We usually call this garbage. Waste is a natural by-product of any process on Earth and cannot be avoided. Nature reuses all of its by-products, with no waste in the end. What is waste for one is useful for another. For example dead leaves decompose to provide nutrients to plants and oxygen released from trees is used by us.

We humans, however, have disturbed this balance by bringing in new problems such as toxic and non-degradable wastes and even nuclear wastes into the environment. Even ‘normal’ solid waste is now a problem because there is too much of it. Studies show that on an average, each person in urban areas produces half a kilogram of garbage each day. This doesn’t include the garbage we make indirectly - through industry, agriculture and mining. Twenty per cent of Indians live in urban areas. This calculates to more than 36 million tons of garbage each year in cities alone !

Though waste generated has increased, the way we deal with the disposal of waste has not changed in over ten thousand years. We pile it and then burn it, or bury it in some out-of-the-way place where we forget about it. But today, we are faced with too much garbage and not enough places left to throw it away. Improper disposal of solid wastes has lead to ground water contamination, air pollution, health hazards etc.

CLEAN-India Helps Manage Waste Better

The members of CLEAN programme are made aware of the glaring (but overlooked) problem of waste in our cities. Activities and film shows have made students aware of the solid waste problem in urban areas and their role in reducing it. Issues like the ill effects of polybags, littering on our streets, excessive consumerism are all discussed and deliberated with student groups. Clean-up drives in local parks and markets are organised in which students very enthusiastically help in cleaning up and drive home the message that adults should not indulge in littering.

With the objective of managing the waste locally through simple techniques, natural composting, vermicomposting, paper recycling and Reuse Society have been initiated in schools and community.

Composting

Composting is, in the broadest terms, the biological reduction of organic wastes to humus. Whenever a plant / animal dies, its remains are attacked by soil micro-organisms and are reduced to an earthlike substance that is beneficial for the growth of plant (roots). This process is repeated universally and continuously in every part of the world, and is a part of the wheel of life.

Two methods of Composting undertaken at the school level are Vermicomposting and Natural Composting.

Natural Composting

In natural composting, the waste decomposes with the aid of other factors such as insects, worms and tiny microbes. This is possible in each and every school, irrespective of the amount of waste they generate. Schools that do not have their own canteens and consequently have little biodegradable waste generated can adopt this project. They can decompose all their garden waste easily by alternatively layering a pit ( 1 m deep, 1 m wide and 1 m.long, as per convenience) with the waste and soil. This form of composting is recommended particularly for those schools which have a lot of garden waste like dried leaves that can be saved from burning. The compost thus generated is used in the school lawns and gardens as a substitute for manure, thus saving the cost of fertilisers.

Vermicomposting

This is the process through which we can convert biodegradable waste into rich humus by using earthworms. After an earthworm ingests organic matter, the matter undergoes chemical changes and what comes out is a rich plant food. This makes our soil fertile and plants stronger. Then we need not buy chemical fertilisers.

Many CLEAN-India schools, that have their own canteens and gardens have adopted this project. Hands-on-experience in vermicomposting shows students effective ways of taking care of biodegradable waste. The project not only solves the problem of solid waste to an extent and gives rich compost in return, it also helps students realize the importance of small creatures like earthworms and helps them shed their fear. In the process it brings alive the concepts learnt in class about decomposition in nature and how earthworms function. In many schools, the compost produced is also sold to the parents. Few schools like Shri Ram and Joseph and Mary in Delhi are now providing earthworms and helping people of nearby villages to initiate their own vermicomposting units.

Re-Use Society

A king once offered five hundred garments to a disciple of Buddha.The king asked the disciple what he would do with so many garments ?The Disciple replied : " Oh King, many of our brothers are in rags:I am going to distribute the garments among brothers."What will you do with the old garments ?We will make bed - covers out of them.What will you do with the old bed - covers ?We will make pillow - cases out of them.What will you do with the old pillow - cases ?We will make floor - covers out of them.What will you do with the old floor - covers ?We will use them for foot towels .What will you do with the old foot - towels ?Your highness, we will tear them into pieces,mix them with mud and use the mud to plaster the house walls.

What is waste for you, is wealth for somebody else. There has been a tradition in India of finding an innovative use for every thing: - tyres, battery cases, plastic bins and what not. A similar thing is started in School which saves both the environment and money in the bargain, in addition to inculcating in students a habit of not discarding things unthinkingly.

Apart from making innovative things from discarded things in the Crafts Period, two major activities are suggested to the school under the Reuse Society. The first activity is to exchange books and even notes at the beginning of each academic session. Students of a senior class give the books to the students of a junior class and, in turn, receive books from the senior section, and a chain is established throughout the school. This way a lot of paper and consequently trees can be saved.

The next major activity in the Reuse Society is to donate books and outgrown clothes, toys, etc. The books / story books /comics that have been read and re-read, the clothes and shoes that have outgrown, are collected in schools and given to the less fortunate children of the society. Such collection is presented to Child Welfare organizations, slums, orphanages etc.

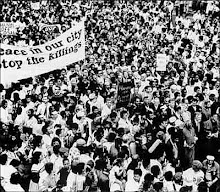

Urban poor increasingly made homeless

Urban poor increasingly made homeless in India’s drive for more ‘beautiful’ cities By Dunu Roy, Combat Law

16 January 2005: When Mumbai (Bombay) Municipal Corporation evicted pavement dwellers in 1981, a journalist came forward to file a public interest petition to protect the rights of the pavement dwellers. After five years in 1986, the case became a landmark judgment that maintained that the Right to Life included the Right to Livelihood. As livelihood of the poor depends directly on where they live, this was a verdict in favour of pavement dwellers.In the early 70s the city passed Slum Clearance Act, while the Slum Upgradation Scheme was conceptualised in the 80s, which later became the Slum Redevelopment Scheme of the 90s. But at the turn of the century the very same metropolis used massive force with helicopters and armed police, to evict 73,000 families from the periphery of the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. This action was in response to Court orders in another ‘public interest’ petition, but filed this time by the Bombay Environmental Action Group (BEAG). What the BEAG appeared to be concerned about was the protection of a 28-square kilometre ‘National’ Park, particularly the one-third reserved for ‘tourism’. But no one seemed to be bothered by either the sundry religious Ashrams inside the Park or the proliferating blocks of private apartment houses on its boundary. What, then, was common to the nature of "public interest" espoused by Tellis and the BEAG, and how did the Court view either or both? And were there any radical social changes in the twenty years that intervened between the two?Urban developmentIn Chennai City 40 per cent of the population lives in slums - there are 69,000 families who have been identified to be living on government land and they are to be relocated to areas far removed from the city. The areas vacated will be taken over by railway tracks, hotel resorts, commercial and residential complexes, and modern businesses. Much of the ‘clearance’ is being undertaken in the name of ‘beautification’ and tourism.In Kolkata (Calcutta) the Left Front government though claims to be pro-poor also is working on ‘environmental improvement’ projects. Operation Sunshine was launched in 1996 to evict over 50,000 hawkers from the city's main streets. Currently over 7,000 hutments are being forcibly demolished along the sides of storm water drains and the metro and circular rail tracks. At the same time, lavish commercial and residential complexes are coming up unhindered along the metropolitan bypass, where the real estate prices rival those in the elite areas of South Calcutta.Delhi, where sub-standard settlements house as much as 70 per cent of the city's population, leads the way in environmental activism. Not only have vendors, cycle-rickshaws, beggars, shanties, polluting and non-conforming industries, and diesel buses already been ‘evicted’, A recent addition to the hit list are the 75,000 families who live on the banks of the Yamuna river. They are being held responsible for the river's pollution.In 1997, Hyderabad was distributing land titles and housing loans to the urban poor, but during the TDP tenure the state had leased large areas of land at heavily subsidized rate to business groups, international airports, cinemas, shopping complexes, hotels, corporate hospitals, and railway tracks. Over 10,000 houses of the ‘weaker members of society’ have been demolished to make way for the new face of ‘Cyber bad’.Urban planning trendsLarge areas of habitation of India’s urban poor have been forcefully taken over by every government - regardless of political make-up. The groups of people affected are often the ones who have been employed in informal sectors or are self-employed in the tertiary services sector. Their displacement is much to do with the space they live in as with the work they perform.The areas that they occupied are being transferred into larger private corporate entities such as commercial complexes and residential developments. These units are also often coupled with labour-replacing devices ranging from automatic tellers and computer-aided machines to vacuum cleaners and home delivery services, thus eliminating the work earlier done by the lower rungs of the urban population.While the driving force behind these changes is manifestly the new globalised economy, it is offered on an environmental platter of ‘cleanliness’ and ‘beautification’.In vicious combination these three trends are changing the urban landscape from ‘homes’ to ‘estate ownerships’ in the name of liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation. Concepts of urban planning too are changing in harmony with these trends although, as we shall see later, the seeds were sown long ago as capitalist empire spread its hegemony over the world.The replacement of housing of poor urban dwellers with commercial and upmarket developments raises several questions about the nature of ‘planning’ itself. Who makes these plans? Who are they made for? Do the planners take into account actual data from the study of how cities grow?Urban planning in DelhiThe Delhi Development Authority (DDA) was constituted in 1957 to check the haphazard and unplanned growth of Delhi... with its sprawling residential colonies, without proper layouts and without the conveniences of life, and to promote and secure the development of Delhi according to plan". For the three years the DDA guided by experts from the Ford Foundation had developed a Master Plan for Delhi for 20 years and this was presented along with maps and charts for unprecedented ‘public’ discussion in 1960. The public debate on this initial document elicited over 600 objections and suggestions from ‘the public, cooperative house-building societies, associations of industrialists, local bodies, and various Ministries and Departments of the Government of India’. An ad-hoc Board was appointed to go into all these objections and it gave its recommendations to the DDA in 1961.Eventually the Master Plan of Delhi was formally sanctioned in 1962. Predictably, the first concern of this Plan was the growth in the urban population and the planners proposed to restrict it by building a 1.6 km wide green belt around the city and diverting the surplus population to the adjacent ‘ring towns’. It was also decided that the ‘congested’ population of the walled city would be relocated in New Delhi and Civil Lines. At the same time several new industrial and commercial areas were declared for promoting growth. Thus, the DDA saw merit in both earning more revenue through industrial expansion as well as reducing expenses by curbing population increase, without examining the necessary linkage between the two.Delhi's expansionBut it was in 1971 that it became clear that the city's growth is far beyond the conception of planners. The total number of industries had increased to 26,000 and there was a huge spurt in the squatter and ‘unauthorized’ settlements. So, in a frantic burst of activity to ‘restore order’, the administrative machinery swung into action and from 1975 to 1977 1.5 Lakh (one lakh = 100,000) squatter families were forcibly moved out of the city into resettlement colonies on the periphery. Each family was entitled to a plot of only 25 square yards with common services and 60,000 such plots were demarcated on the low-lying Yamuna flood plain alone. Interestingly enough, all the resettlements were located very near the new industrial and residential areas, presumably designed to provide cheap and docile labour. This labour force was further enlarged by another 10 lakhs in 1982 when the Asian Games overtook the city. Numerous stadiums, shops, roads, hotels, flyovers, offices, apartments, and colonies were constructed to cater to the needs of the Games and the anticipated commercial spillover. The second Ring Road became a magnet for further commercial and residential development. But the city could not cope with this additional burden.In 1985, the National Capital Region Board was set up to plan for a balanced growth of extended region around the capital. Also in 1985, the second master plan draft was published for comments. However, unlike the first plan, this one was not summarized or translated into Hindi and Urdu, nor it was distributed publicly. Nevertheless, the draft came in for severe criticism from the government itself as being ‘conceptually defective’ and the Delhi Urban Arts Commission (DUAC) was asked to prepare another plan. The DUAC took a close look at the failures of the first master plan to detail its own conceptual plan. But their plan was also rejected by DDA and there was no public hearing, but the draft was discussed in the select committee. In order to avoid public consultation and parliamentary debate, it was decided that the second plan would only be ‘precisely a comprehensive revision of the first one’.This revised version identified that major part of the city's problems originated outside and their solutions lay beyond its territory. It too recommended for de-industrialization, maintenance of ecological balance in the Ridge and the Yamuna, decentralisation into districts, and provision of multi-nodal mass transport, with low-rise high-density urbanization. Interestingly enough, it called for a special area status for the walled city as "it cannot be developed on the basis of normal planning policies and controls". In fact the planners did not even understand the implications of what they themselves had done. For example in 1988 during the cholera outbreak 1500 people died in the 44 resettlement colonies they had planned in 1975. It was recognized that the disease had spread through ground water contamination by inadequate sanitation measures in the low-lying areas but an embarrassed administration shied away from being held responsible. Thus, the new plan not only failed in tackling the problems, but also they did not even incorporate their own analysis of failures and weaknesses of past planning into its recommendations.As the date for yet another Master Plan approaches, this systemic failure of modern planning is evident in the situation as it obtains today. Delhi has spread far beyond the confines of the Outer Ring Road. The original green belt has largely fallen victim to land developers, including the DDA itself. The resettlement colonies and industrial areas, that were once supposed to be at the fringe of the city, have been drawn into its ambit. The ring towns are now contiguous urban sprawls and the arterial roads and national highways are the most congested in the region. Increasing numbers of poor inhabitants continue to live in shantytowns without services. It is presently estimated that around 60 percent of the population live in sub-standard housing. Rapidly shrinking employment opportunities and crusading environmental activism have made the situation significantly worse for them. While the city gets the Clean City Award from far-off California, it's own citizens grimly face critical inadequacies of work, shelter, civic amenities and governance.The guidelines for the new plan issued by the Ministry of Urban Development refuse to address these issues. Instead they focus on how to promote private participation and market competition in land, housing, and services; how to protect heritage, encourage tourism, and increase revenues; and how to obey the twin dictates of military order and profitable commerce. The fact is that the planners have not learnt any lessons from past disasters, such as the jaundice and cholera epidemics and the Asian Games. The jubilant and manipulated voices that accompany the announcement of the Yamuna canalisation plans and the gigantic mall on the Ridge and the looming Commonwealth Games testifies to the total bankruptcy and arrogance of the overall city planning process.

16 January 2005: When Mumbai (Bombay) Municipal Corporation evicted pavement dwellers in 1981, a journalist came forward to file a public interest petition to protect the rights of the pavement dwellers. After five years in 1986, the case became a landmark judgment that maintained that the Right to Life included the Right to Livelihood. As livelihood of the poor depends directly on where they live, this was a verdict in favour of pavement dwellers.In the early 70s the city passed Slum Clearance Act, while the Slum Upgradation Scheme was conceptualised in the 80s, which later became the Slum Redevelopment Scheme of the 90s. But at the turn of the century the very same metropolis used massive force with helicopters and armed police, to evict 73,000 families from the periphery of the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. This action was in response to Court orders in another ‘public interest’ petition, but filed this time by the Bombay Environmental Action Group (BEAG). What the BEAG appeared to be concerned about was the protection of a 28-square kilometre ‘National’ Park, particularly the one-third reserved for ‘tourism’. But no one seemed to be bothered by either the sundry religious Ashrams inside the Park or the proliferating blocks of private apartment houses on its boundary. What, then, was common to the nature of "public interest" espoused by Tellis and the BEAG, and how did the Court view either or both? And were there any radical social changes in the twenty years that intervened between the two?Urban developmentIn Chennai City 40 per cent of the population lives in slums - there are 69,000 families who have been identified to be living on government land and they are to be relocated to areas far removed from the city. The areas vacated will be taken over by railway tracks, hotel resorts, commercial and residential complexes, and modern businesses. Much of the ‘clearance’ is being undertaken in the name of ‘beautification’ and tourism.In Kolkata (Calcutta) the Left Front government though claims to be pro-poor also is working on ‘environmental improvement’ projects. Operation Sunshine was launched in 1996 to evict over 50,000 hawkers from the city's main streets. Currently over 7,000 hutments are being forcibly demolished along the sides of storm water drains and the metro and circular rail tracks. At the same time, lavish commercial and residential complexes are coming up unhindered along the metropolitan bypass, where the real estate prices rival those in the elite areas of South Calcutta.Delhi, where sub-standard settlements house as much as 70 per cent of the city's population, leads the way in environmental activism. Not only have vendors, cycle-rickshaws, beggars, shanties, polluting and non-conforming industries, and diesel buses already been ‘evicted’, A recent addition to the hit list are the 75,000 families who live on the banks of the Yamuna river. They are being held responsible for the river's pollution.In 1997, Hyderabad was distributing land titles and housing loans to the urban poor, but during the TDP tenure the state had leased large areas of land at heavily subsidized rate to business groups, international airports, cinemas, shopping complexes, hotels, corporate hospitals, and railway tracks. Over 10,000 houses of the ‘weaker members of society’ have been demolished to make way for the new face of ‘Cyber bad’.Urban planning trendsLarge areas of habitation of India’s urban poor have been forcefully taken over by every government - regardless of political make-up. The groups of people affected are often the ones who have been employed in informal sectors or are self-employed in the tertiary services sector. Their displacement is much to do with the space they live in as with the work they perform.The areas that they occupied are being transferred into larger private corporate entities such as commercial complexes and residential developments. These units are also often coupled with labour-replacing devices ranging from automatic tellers and computer-aided machines to vacuum cleaners and home delivery services, thus eliminating the work earlier done by the lower rungs of the urban population.While the driving force behind these changes is manifestly the new globalised economy, it is offered on an environmental platter of ‘cleanliness’ and ‘beautification’.In vicious combination these three trends are changing the urban landscape from ‘homes’ to ‘estate ownerships’ in the name of liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation. Concepts of urban planning too are changing in harmony with these trends although, as we shall see later, the seeds were sown long ago as capitalist empire spread its hegemony over the world.The replacement of housing of poor urban dwellers with commercial and upmarket developments raises several questions about the nature of ‘planning’ itself. Who makes these plans? Who are they made for? Do the planners take into account actual data from the study of how cities grow?Urban planning in DelhiThe Delhi Development Authority (DDA) was constituted in 1957 to check the haphazard and unplanned growth of Delhi... with its sprawling residential colonies, without proper layouts and without the conveniences of life, and to promote and secure the development of Delhi according to plan". For the three years the DDA guided by experts from the Ford Foundation had developed a Master Plan for Delhi for 20 years and this was presented along with maps and charts for unprecedented ‘public’ discussion in 1960. The public debate on this initial document elicited over 600 objections and suggestions from ‘the public, cooperative house-building societies, associations of industrialists, local bodies, and various Ministries and Departments of the Government of India’. An ad-hoc Board was appointed to go into all these objections and it gave its recommendations to the DDA in 1961.Eventually the Master Plan of Delhi was formally sanctioned in 1962. Predictably, the first concern of this Plan was the growth in the urban population and the planners proposed to restrict it by building a 1.6 km wide green belt around the city and diverting the surplus population to the adjacent ‘ring towns’. It was also decided that the ‘congested’ population of the walled city would be relocated in New Delhi and Civil Lines. At the same time several new industrial and commercial areas were declared for promoting growth. Thus, the DDA saw merit in both earning more revenue through industrial expansion as well as reducing expenses by curbing population increase, without examining the necessary linkage between the two.Delhi's expansionBut it was in 1971 that it became clear that the city's growth is far beyond the conception of planners. The total number of industries had increased to 26,000 and there was a huge spurt in the squatter and ‘unauthorized’ settlements. So, in a frantic burst of activity to ‘restore order’, the administrative machinery swung into action and from 1975 to 1977 1.5 Lakh (one lakh = 100,000) squatter families were forcibly moved out of the city into resettlement colonies on the periphery. Each family was entitled to a plot of only 25 square yards with common services and 60,000 such plots were demarcated on the low-lying Yamuna flood plain alone. Interestingly enough, all the resettlements were located very near the new industrial and residential areas, presumably designed to provide cheap and docile labour. This labour force was further enlarged by another 10 lakhs in 1982 when the Asian Games overtook the city. Numerous stadiums, shops, roads, hotels, flyovers, offices, apartments, and colonies were constructed to cater to the needs of the Games and the anticipated commercial spillover. The second Ring Road became a magnet for further commercial and residential development. But the city could not cope with this additional burden.In 1985, the National Capital Region Board was set up to plan for a balanced growth of extended region around the capital. Also in 1985, the second master plan draft was published for comments. However, unlike the first plan, this one was not summarized or translated into Hindi and Urdu, nor it was distributed publicly. Nevertheless, the draft came in for severe criticism from the government itself as being ‘conceptually defective’ and the Delhi Urban Arts Commission (DUAC) was asked to prepare another plan. The DUAC took a close look at the failures of the first master plan to detail its own conceptual plan. But their plan was also rejected by DDA and there was no public hearing, but the draft was discussed in the select committee. In order to avoid public consultation and parliamentary debate, it was decided that the second plan would only be ‘precisely a comprehensive revision of the first one’.This revised version identified that major part of the city's problems originated outside and their solutions lay beyond its territory. It too recommended for de-industrialization, maintenance of ecological balance in the Ridge and the Yamuna, decentralisation into districts, and provision of multi-nodal mass transport, with low-rise high-density urbanization. Interestingly enough, it called for a special area status for the walled city as "it cannot be developed on the basis of normal planning policies and controls". In fact the planners did not even understand the implications of what they themselves had done. For example in 1988 during the cholera outbreak 1500 people died in the 44 resettlement colonies they had planned in 1975. It was recognized that the disease had spread through ground water contamination by inadequate sanitation measures in the low-lying areas but an embarrassed administration shied away from being held responsible. Thus, the new plan not only failed in tackling the problems, but also they did not even incorporate their own analysis of failures and weaknesses of past planning into its recommendations.As the date for yet another Master Plan approaches, this systemic failure of modern planning is evident in the situation as it obtains today. Delhi has spread far beyond the confines of the Outer Ring Road. The original green belt has largely fallen victim to land developers, including the DDA itself. The resettlement colonies and industrial areas, that were once supposed to be at the fringe of the city, have been drawn into its ambit. The ring towns are now contiguous urban sprawls and the arterial roads and national highways are the most congested in the region. Increasing numbers of poor inhabitants continue to live in shantytowns without services. It is presently estimated that around 60 percent of the population live in sub-standard housing. Rapidly shrinking employment opportunities and crusading environmental activism have made the situation significantly worse for them. While the city gets the Clean City Award from far-off California, it's own citizens grimly face critical inadequacies of work, shelter, civic amenities and governance.The guidelines for the new plan issued by the Ministry of Urban Development refuse to address these issues. Instead they focus on how to promote private participation and market competition in land, housing, and services; how to protect heritage, encourage tourism, and increase revenues; and how to obey the twin dictates of military order and profitable commerce. The fact is that the planners have not learnt any lessons from past disasters, such as the jaundice and cholera epidemics and the Asian Games. The jubilant and manipulated voices that accompany the announcement of the Yamuna canalisation plans and the gigantic mall on the Ridge and the looming Commonwealth Games testifies to the total bankruptcy and arrogance of the overall city planning process.

INDIAN TRIBES POPULATION STUDY

Composition and Location - India tribal Population

Indian tribes constitute roughly 8 percent of the nation's total population, nearly 68 million people according to the 1991 census. One concentration lives in a belt along the Himalayas stretching through Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh in the west, to Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Manipur, and Nagaland in the northeast (see fig. 1). Another concentration lives in the hilly areas of central India (Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, and, to a lesser extent, Andhra Pradesh); in this belt, which is bounded by the Narmada River to the north and the Godavari River to the southeast, tribal peoples occupy the slopes of the region's mountains. Other tribals, the Santals, live in Bihar and West Bengal. There are smaller numbers of tribal people in Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala, in western India in Gujarat and Rajasthan, and in the union territories of Lakshadweep and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The extent to which a state's population is tribal varies considerably. In the northeastern states of Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Nagaland, upward of 90 percent of the population is tribal. However, in the remaining northeast states of Assam, Manipur, Sikkim, and Tripura, tribal peoples form between 20 and 30 percent of the population. The largest tribes are found in central India, although the tribal population there accounts for only around 10 percent of the region's total population. Major concentrations of tribal people live in Maharashtra, Orissa, and West Bengal. In the south, about 1 percent of the populations of Kerala and Tamil Nadu are tribal, whereas about 6 percent in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka are members of tribes.

There are some 573 communities recognized by the government as Scheduled Tribes and therefore eligible to receive special benefits and to compete for reserved seats in legislatures and schools. They range in size from the Gonds (roughly 7.4 million) and the Santals (approximately 4.2 million) to only eighteen Chaimals in the Andaman Islands. Central Indian states have the country's largest tribes, and, taken as a whole, roughly 75 percent of the total tribal population live there.

Apart from the use of strictly legal criteria, however, the problem of determining which groups and individuals are tribal is both subtle and complex. Because it concerns economic interests and the size and location of voting blocs, the question of who are members of Scheduled Tribes rather than Backward Classes (see Glossary) or Scheduled Castes (see Glossary) is often controversial. The apparently wide fluctuation in estimates of South Asia's tribal population through the twentieth century gives a sense of how unclear the distinction between tribal and nontribal can be. India's 1931 census enumerated 22 million tribal people, in 1941 only 10 million were counted, but by 1961 some 30 million and in 1991 nearly 68 million tribal members were included. The differences among the figures reflect changing census criteria and the economic incentives individuals have to maintain or reject classification as a tribal member.

These gyrations of census data serve to underline the complex relationship between caste and tribe. Although, in theory, these terms represent different ways of life and ideal types, in reality they stand for a continuum of social groups. In areas of substantial contact between tribes and castes, social and cultural pressures have often tended to move tribes in the direction of becoming castes over a period of years. Tribal peoples with ambitions for social advancement in Indian society at large have tried to gain the classification of caste for their tribes; such efforts conform to the ancient Indian traditions of caste mobility (see Caste and Class, ch. 5). Where tribal leaders prospered, they could hire Brahman priests to construct credible pedigrees and thereby join reasonably high-status castes. On occasion, an entire tribe or part of a tribe joined a Hindu sect and thus entered the caste system en masse. If a specific tribe engaged in practices that Hindus deemed polluting, the tribe's status when it was assimilated into the caste hierarchy would be affected.

Since independence, however, the special benefits available to Scheduled Tribes have convinced many groups, even Hindus and Muslims, that they will enjoy greater advantages if so designated. The schedule gives tribal people incentives to maintain their identity. By the same token, the schedule also includes a number of groups whose "tribal" status, in cultural terms, is dubious at best; in various districts, the list includes Muslims and a congeries of Hindu castes whose main claim seems to be their ability to deliver votes to the party that arranges their listing among the Scheduled Tribes.

A number of traits have customarily been seen as establishing tribal rather than caste identity. These include language, social organization, religious affiliation, economic patterns, geographic location, and self-identification. Recognized tribes typically live in hilly regions somewhat remote from caste settlements; they generally speak a language recognized as tribal.

Unlike castes, which are part of a complex and interrelated local economic exchange system, tribes tend to form self-sufficient economic units. Often they practice swidden farming--clearing a field by slash-and-burn methods, planting it for a number of seasons, and then abandoning it for a lengthy fallow period--rather than the intensive farming typical of most of rural India. For most tribal people, land-use rights traditionally derive simply from tribal membership. Tribal society tends to be egalitarian, its leadership being based on ties of kinship and personality rather than on hereditary status. Tribes typically consist of segmentary lineages whose extended families provide the basis for social organization and control. Unlike caste religion, which recognizes the hegemony of Brahman priests, tribal religion recognizes no authority outside the tribe.

Any of these criteria can be called into question in specific instances. Language is not always an accurate indicator of tribal or caste status. Especially in regions of mixed population, many tribal groups have lost their mother tongues and simply speak local or regional languages. Linguistic assimilation is an ongoing process of considerable complexity. In the highlands of Orissa, for example, the Bondos--a Munda-language-speaking tribe--use their own tongue among themselves. Oriya, however, serves as a lingua franca in dealings with Hindu neighbors. Oriya as a prestige language (in the Bondo view), however, has also supplanted the native tongue as the language of ritual. In parts of Assam, historically divided into warring tribes and villages, increased contact among villagers began during the colonial period and has accelerated since independence. A pidgin Assamese developed while educated tribal members learned Hindi and, in the late twentieth century, English.

Self-identification and group loyalty are not unfailing markers of tribal identity either. In the case of stratified tribes, the loyalties of clan, kin, and family may well predominate over those of tribe. In addition, tribes cannot always be viewed as people living apart; the degree of isolation of various tribes has varied tremendously. The Gonds, Santals, and Bhils traditionally have dominated the regions in which they have lived. Moreover, tribal society is not always more egalitarian than the rest of the rural populace; some of the larger tribes, such as the Gonds, are highly stratified.

Economic and Political Conditions

Most Indian tribes are concentrated in heavily forested areas that combine inaccessibility with limited political or economic significance. Historically, the economy of most tribes was subsistence agriculture or hunting and gathering. Tribal members traded with outsiders for the few necessities they lacked, such as salt and iron. A few local Hindu craftsmen might provide such items as cooking utensils. The twentieth century, however, has seen far-reaching changes in the relationship between tribals in India and the larger society and, by extension, traditional tribal economies. Improved transportation and communications have brought ever deeper intrusions into tribal lands; merchants and a variety of government policies have involved tribal peoples more thoroughly in the cash economy, although by no means on the most favorable of terms. Large areas fell into the hands of nontribals around 1900, when many regions were opened by the government to homestead-style settlement. Immigrants received free land in return for cultivating it. Tribal people, too, could apply for land titles, although even title to the portion of land they happened to be planting that season could not guarantee their ability to continue swidden cultivation. More important, the notion of permanent, individual ownership of land was foreign to most tribals. Land, if seen in terms of ownership at all, was viewed as a communal resource, free to whoever needed it. By the time tribals accepted the necessity of obtaining formal land titles, they had lost the opportunity to lay claim to lands that might rightfully have been considered theirs. Generally, tribals were severely disadvantaged in dealing with government officials who granted land titles. Albeit belatedly, the colonial regime realized the necessity of protecting tribals of India from the predations of outsiders and prohibited the sale of tribal lands. Although an important loophole in the form of land leases was left open, tribes made some gains in the mid-twentieth century. Despite considerable obstruction by local police and land officials, who were slow to delineate tribal holdings and slower still to offer police protection, some land was returned to tribal peoples.

In the 1970s, the gains tribal peoples had made in earlier decades were eroded in many regions, especially in central India. Migration into tribal lands increased dramatically, and the deadly combination of constabulary and revenue officers uninterested in tribal welfare and sophisticated nontribals willing and able to bribe local officials was sufficient to deprive many tribals of their landholdings. The means of subverting protective legislation were legion: local officials could be persuaded to ignore land acquisition by nontribal people, alter land registry records, lease plots of land for short periods and then simply refuse to relinquish them, or induce tribal members to become indebted and attach their lands. Whatever the means, the result was that many tribal members became landless laborers in the 1960s and 1970s, and regions that a few years earlier had been the exclusive domain of tribes had an increasingly heterogeneous population. Unlike previous eras in which tribal people were shunted into more remote forests, by the 1960s relatively little unoccupied land was available. Government efforts to evict nontribal members from illegal occupation have proceeded slowly; when evictions occur at all, those ejected are usually members of poor, lower castes. In a 1985 publication, anthropologist Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf describes this process in Andhra Pradesh: on average only 25 to 33 percent of the tribal families in such villages had managed to keep even a portion of their holdings. Outsiders had paid about 5 percent of the market value of the lands they took.

Improved communications, roads with motorized traffic, and more frequent government intervention figured in the increased contact that tribal peoples had with outsiders. Tribes fared best where there was little to induce nontribals to settle; cash crops and commercial highways frequently signaled the dismemberment of the tribes. Merchants have long been a link to the outside world, but in the past they were generally petty traders, and the contact they had with tribal people was transient. By the 1960s and 1970s, the resident nontribal shopkeeper was a permanent feature of many villages. Shopkeepers often sold liquor on credit, enticing tribal members into debt and into mortgaging their land. In the past, tribes made up shortages before harvest by foraging from the surrounding forest. More recently shopkeepers have offered ready credit--with the proviso that loans be repaid in kind with 50 to 100 percent interest after harvest. Repaying one bag of millet with two bags has set up a cycle of indebtedness from which many have been unable to break loose.

The possibility of cultivators growing a profitable cash crop, such as cotton or castor-oil plants, continues to draw merchants into tribal areas. Nontribal traders frequently establish an extensive network of relatives and associates as shopkeepers to serve as agents in a number of villages. Cultivators who grow a cash crop often sell to the same merchants, who provide consumption credit throughout the year. The credit carries a high-interest price tag, whereas the tribal peoples' crops are bought at a fraction of the market rate. Cash crops offer a further disadvantage in that they decrease the supply of available foodstuffs and increase tribal dependence on economic forces beyond their control. This transformation has meant a decline in both the tribes' security and their standard of living.

In previous generations, families might have purchased silver jewelry as a form of security; contemporary tribal people are more likely to buy minor consumer goods. Whereas jewelry could serve as collateral in critical emergencies, current purchases simply increase indebtedness. In areas where gathering forest products is remunerative, merchants exchange their products for tribal labor. Indebtedness is so extensive that although such transactions are illegal, traders sometimes "sell" their debtors to other merchants, much like indentured servants.

In some instances, tribes have managed to hold their own in contacts with outsiders. Some Chenchus, a hunting and gathering tribe of the central hill regions of Andhra Pradesh, have continued to specialize in collecting forest products for sale. Caste Hindus living among them rent land from the Chenchus and pay a portion of the harvest. The Chenchus themselves have responded unenthusiastically to government efforts to induce them to take up farming. Their relationship to nontribal people has been one of symbiosis, although there were indications in the early 1980s that other groups were beginning to compete with the Chenchus in gathering forest products. A large paper mill was cutting bamboo in their territory in a manner that did not allow regeneration, and two groups had begun to collect for sale the same products the Chenchus sell. Dalits settled among them with the help of the Chenchus and learned agriculture from them. The nomadic Banjara herders who graze their cattle in the forest also have been allotted land there. The Chenchus have a certain advantage in dealing with caste Hindus; because of their long association with Hindu hermits and their refusal to eat beef, they are considered an unpolluted caste. Other tribes, particularly in South India, have cultural practices that are offensive to Hindus and, when they are assimilated, are often considered Dalits.

The final blow for some tribes has come when nontribals, through political jockeying, have managed to gain legal tribal status, that is, to be listed as a Scheduled Tribe. The Gonds of Andhra Pradesh effectively lost their only advantage in trying to protect their lands when the Banjaras, a group that had been settling in Gond territory, were classified as a Scheduled Tribe in 1977. Their newly acquired tribal status made the Banjaras eligible to acquire Gond land "legally" and to compete with Gonds for reserved political seats, places in education institutions, and other benefits. Because the Banjaras are not scheduled in neighboring Maharashtra, there has been an influx of Banjara emigrants from that state into Andhra Pradesh in search of better opportunities.

Tribes in the Himalayan foothills have not been as hard-pressed by the intrusions of nontribals. Historically, their political status was always distinct from the rest of India. Until the British colonial period, there was little effective control by any of the empires centered in peninsular India; the region was populated by autonomous feuding tribes. The British, in efforts to protect the sensitive northeast frontier, followed a policy dubbed the "Inner Line"; nontribal people were allowed into the areas only with special permission. Postindependence governments have continued the policy, protecting the Himalayan tribes as part of the strategy to secure the border with China (see Principal Regions, ch. 2).

This policy has generally saved the northern tribes from the kind of exploitation that those elsewhere in South Asia have suffered. In Arunachal Pradesh (formerly part of the North-East Frontier Agency), for example, tribal members control commerce and most lower-level administrative posts. Government construction projects in the region have provided tribes with a significant source of cash--both for setting up businesses and for providing paying customers. Some tribes have made rapid progress through the education system. Instruction was begun in Assamese but was eventually changed to Hindi; by the early 1980s, English was taught at most levels. Both education and the increase in ready cash from government spending have permitted tribal people a significant measure of social mobility. The role of early missionaries in providing education was also crucial in Assam.

Government policies on forest reserves have affected tribal peoples profoundly. Wherever the state has chosen to exploit forests, it has seriously undermined the tribes' way of life. Government efforts to reserve forests have precipitated armed (if futile) resistance on the part of the tribal peoples involved. Intensive exploitation of forests has often meant allowing outsiders to cut large areas of trees (while the original tribal inhabitants were restricted from cutting), and ultimately replacing mixed forests capable of sustaining tribal life with single-product plantations. Where forests are reserved, nontribals have proved far more sophisticated than their forest counterparts at bribing the necessary local officials to secure effective (if extralegal) use of forestlands. The system of bribing local officials charged with enforcing the reserves is so well established that the rates of bribery are reasonably fixed (by the number of plows a farmer uses or the amount of grain harvested). Tribal people often end up doing unpaid work for Hindus simply because a caste Hindu, who has paid the requisite bribe, can at least ensure a tribal member that he or she will not be evicted from forestlands. The final irony, notes von Fürer-Haimendorf, is that the swidden cultivation many tribes practiced had maintained South Asia's forests, whereas the intensive cultivating and commercial interests that replaced the tribal way of life have destroyed the forests (see Forestry, ch. 7).

Extending the system of primary education into tribal areas and reserving places for tribal children in middle and high schools and higher education institutions are central to government policy, but efforts to improve a tribe's educational status have had mixed results (see Education, ch. 2). Recruitment of qualified teachers and determination of the appropriate language of instruction also remain troublesome. Commission after commission on the "language question" has called for instruction, at least at the primary level, in the students' native tongue. In some regions, tribal children entering school must begin by learning the official regional language, often one completely unrelated to their tribal tongue. The experiences of the Gonds of Andhra Pradesh provide an example. Primary schooling began there in the 1940s and 1950s. The government selected a group of Gonds who had managed to become semiliterate in Telugu and taught them the basics of written script. These individuals became teachers who taught in Gondi, and their efforts enjoyed a measure of success until the 1970s, when state policy demanded instruction in Telugu. The switch in the language of instruction both made the Gond teachers superfluous because they could not teach in Telugu and also presented the government with the problem of finding reasonably qualified teachers willing to teach in outlying tribal schools.

The commitment of tribes to acquiring a formal education for their children varies considerably. Tribes differ in the extent to which they view education positively. Gonds and Pardhans, two groups in the central hill region, are a case in point. The Gonds are cultivators, and they frequently are reluctant to send their children to school, needing them, they say, to work in the fields. The Pardhans were traditionally bards and ritual specialists, and they have taken to education with enthusiasm. The effectiveness of educational policy likewise varies by region. In those parts of the northeast where tribes have generally been spared the wholesale onslaught of outsiders, schooling has helped tribal people to secure political and economic benefits. The education system there has provided a corps of highly trained tribal members in the professions and high-ranking administrative posts.

Many tribal schools are plagued by high dropout rates. Children attend for the first three to four years of primary school and gain a smattering of knowledge, only to lapse into illiteracy later. Few who enter continue up to the tenth grade; of those who do, few manage to finish high school. Therefore, very few are eligible to attend institutions of higher education, where the high rate of attrition continues.

Indian tribes constitute roughly 8 percent of the nation's total population, nearly 68 million people according to the 1991 census. One concentration lives in a belt along the Himalayas stretching through Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh in the west, to Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Manipur, and Nagaland in the northeast (see fig. 1). Another concentration lives in the hilly areas of central India (Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, and, to a lesser extent, Andhra Pradesh); in this belt, which is bounded by the Narmada River to the north and the Godavari River to the southeast, tribal peoples occupy the slopes of the region's mountains. Other tribals, the Santals, live in Bihar and West Bengal. There are smaller numbers of tribal people in Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala, in western India in Gujarat and Rajasthan, and in the union territories of Lakshadweep and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The extent to which a state's population is tribal varies considerably. In the northeastern states of Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Nagaland, upward of 90 percent of the population is tribal. However, in the remaining northeast states of Assam, Manipur, Sikkim, and Tripura, tribal peoples form between 20 and 30 percent of the population. The largest tribes are found in central India, although the tribal population there accounts for only around 10 percent of the region's total population. Major concentrations of tribal people live in Maharashtra, Orissa, and West Bengal. In the south, about 1 percent of the populations of Kerala and Tamil Nadu are tribal, whereas about 6 percent in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka are members of tribes.

There are some 573 communities recognized by the government as Scheduled Tribes and therefore eligible to receive special benefits and to compete for reserved seats in legislatures and schools. They range in size from the Gonds (roughly 7.4 million) and the Santals (approximately 4.2 million) to only eighteen Chaimals in the Andaman Islands. Central Indian states have the country's largest tribes, and, taken as a whole, roughly 75 percent of the total tribal population live there.

Apart from the use of strictly legal criteria, however, the problem of determining which groups and individuals are tribal is both subtle and complex. Because it concerns economic interests and the size and location of voting blocs, the question of who are members of Scheduled Tribes rather than Backward Classes (see Glossary) or Scheduled Castes (see Glossary) is often controversial. The apparently wide fluctuation in estimates of South Asia's tribal population through the twentieth century gives a sense of how unclear the distinction between tribal and nontribal can be. India's 1931 census enumerated 22 million tribal people, in 1941 only 10 million were counted, but by 1961 some 30 million and in 1991 nearly 68 million tribal members were included. The differences among the figures reflect changing census criteria and the economic incentives individuals have to maintain or reject classification as a tribal member.

These gyrations of census data serve to underline the complex relationship between caste and tribe. Although, in theory, these terms represent different ways of life and ideal types, in reality they stand for a continuum of social groups. In areas of substantial contact between tribes and castes, social and cultural pressures have often tended to move tribes in the direction of becoming castes over a period of years. Tribal peoples with ambitions for social advancement in Indian society at large have tried to gain the classification of caste for their tribes; such efforts conform to the ancient Indian traditions of caste mobility (see Caste and Class, ch. 5). Where tribal leaders prospered, they could hire Brahman priests to construct credible pedigrees and thereby join reasonably high-status castes. On occasion, an entire tribe or part of a tribe joined a Hindu sect and thus entered the caste system en masse. If a specific tribe engaged in practices that Hindus deemed polluting, the tribe's status when it was assimilated into the caste hierarchy would be affected.

Since independence, however, the special benefits available to Scheduled Tribes have convinced many groups, even Hindus and Muslims, that they will enjoy greater advantages if so designated. The schedule gives tribal people incentives to maintain their identity. By the same token, the schedule also includes a number of groups whose "tribal" status, in cultural terms, is dubious at best; in various districts, the list includes Muslims and a congeries of Hindu castes whose main claim seems to be their ability to deliver votes to the party that arranges their listing among the Scheduled Tribes.

A number of traits have customarily been seen as establishing tribal rather than caste identity. These include language, social organization, religious affiliation, economic patterns, geographic location, and self-identification. Recognized tribes typically live in hilly regions somewhat remote from caste settlements; they generally speak a language recognized as tribal.

Unlike castes, which are part of a complex and interrelated local economic exchange system, tribes tend to form self-sufficient economic units. Often they practice swidden farming--clearing a field by slash-and-burn methods, planting it for a number of seasons, and then abandoning it for a lengthy fallow period--rather than the intensive farming typical of most of rural India. For most tribal people, land-use rights traditionally derive simply from tribal membership. Tribal society tends to be egalitarian, its leadership being based on ties of kinship and personality rather than on hereditary status. Tribes typically consist of segmentary lineages whose extended families provide the basis for social organization and control. Unlike caste religion, which recognizes the hegemony of Brahman priests, tribal religion recognizes no authority outside the tribe.

Any of these criteria can be called into question in specific instances. Language is not always an accurate indicator of tribal or caste status. Especially in regions of mixed population, many tribal groups have lost their mother tongues and simply speak local or regional languages. Linguistic assimilation is an ongoing process of considerable complexity. In the highlands of Orissa, for example, the Bondos--a Munda-language-speaking tribe--use their own tongue among themselves. Oriya, however, serves as a lingua franca in dealings with Hindu neighbors. Oriya as a prestige language (in the Bondo view), however, has also supplanted the native tongue as the language of ritual. In parts of Assam, historically divided into warring tribes and villages, increased contact among villagers began during the colonial period and has accelerated since independence. A pidgin Assamese developed while educated tribal members learned Hindi and, in the late twentieth century, English.

Self-identification and group loyalty are not unfailing markers of tribal identity either. In the case of stratified tribes, the loyalties of clan, kin, and family may well predominate over those of tribe. In addition, tribes cannot always be viewed as people living apart; the degree of isolation of various tribes has varied tremendously. The Gonds, Santals, and Bhils traditionally have dominated the regions in which they have lived. Moreover, tribal society is not always more egalitarian than the rest of the rural populace; some of the larger tribes, such as the Gonds, are highly stratified.

Economic and Political Conditions

Most Indian tribes are concentrated in heavily forested areas that combine inaccessibility with limited political or economic significance. Historically, the economy of most tribes was subsistence agriculture or hunting and gathering. Tribal members traded with outsiders for the few necessities they lacked, such as salt and iron. A few local Hindu craftsmen might provide such items as cooking utensils. The twentieth century, however, has seen far-reaching changes in the relationship between tribals in India and the larger society and, by extension, traditional tribal economies. Improved transportation and communications have brought ever deeper intrusions into tribal lands; merchants and a variety of government policies have involved tribal peoples more thoroughly in the cash economy, although by no means on the most favorable of terms. Large areas fell into the hands of nontribals around 1900, when many regions were opened by the government to homestead-style settlement. Immigrants received free land in return for cultivating it. Tribal people, too, could apply for land titles, although even title to the portion of land they happened to be planting that season could not guarantee their ability to continue swidden cultivation. More important, the notion of permanent, individual ownership of land was foreign to most tribals. Land, if seen in terms of ownership at all, was viewed as a communal resource, free to whoever needed it. By the time tribals accepted the necessity of obtaining formal land titles, they had lost the opportunity to lay claim to lands that might rightfully have been considered theirs. Generally, tribals were severely disadvantaged in dealing with government officials who granted land titles. Albeit belatedly, the colonial regime realized the necessity of protecting tribals of India from the predations of outsiders and prohibited the sale of tribal lands. Although an important loophole in the form of land leases was left open, tribes made some gains in the mid-twentieth century. Despite considerable obstruction by local police and land officials, who were slow to delineate tribal holdings and slower still to offer police protection, some land was returned to tribal peoples.

In the 1970s, the gains tribal peoples had made in earlier decades were eroded in many regions, especially in central India. Migration into tribal lands increased dramatically, and the deadly combination of constabulary and revenue officers uninterested in tribal welfare and sophisticated nontribals willing and able to bribe local officials was sufficient to deprive many tribals of their landholdings. The means of subverting protective legislation were legion: local officials could be persuaded to ignore land acquisition by nontribal people, alter land registry records, lease plots of land for short periods and then simply refuse to relinquish them, or induce tribal members to become indebted and attach their lands. Whatever the means, the result was that many tribal members became landless laborers in the 1960s and 1970s, and regions that a few years earlier had been the exclusive domain of tribes had an increasingly heterogeneous population. Unlike previous eras in which tribal people were shunted into more remote forests, by the 1960s relatively little unoccupied land was available. Government efforts to evict nontribal members from illegal occupation have proceeded slowly; when evictions occur at all, those ejected are usually members of poor, lower castes. In a 1985 publication, anthropologist Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf describes this process in Andhra Pradesh: on average only 25 to 33 percent of the tribal families in such villages had managed to keep even a portion of their holdings. Outsiders had paid about 5 percent of the market value of the lands they took.

Improved communications, roads with motorized traffic, and more frequent government intervention figured in the increased contact that tribal peoples had with outsiders. Tribes fared best where there was little to induce nontribals to settle; cash crops and commercial highways frequently signaled the dismemberment of the tribes. Merchants have long been a link to the outside world, but in the past they were generally petty traders, and the contact they had with tribal people was transient. By the 1960s and 1970s, the resident nontribal shopkeeper was a permanent feature of many villages. Shopkeepers often sold liquor on credit, enticing tribal members into debt and into mortgaging their land. In the past, tribes made up shortages before harvest by foraging from the surrounding forest. More recently shopkeepers have offered ready credit--with the proviso that loans be repaid in kind with 50 to 100 percent interest after harvest. Repaying one bag of millet with two bags has set up a cycle of indebtedness from which many have been unable to break loose.

The possibility of cultivators growing a profitable cash crop, such as cotton or castor-oil plants, continues to draw merchants into tribal areas. Nontribal traders frequently establish an extensive network of relatives and associates as shopkeepers to serve as agents in a number of villages. Cultivators who grow a cash crop often sell to the same merchants, who provide consumption credit throughout the year. The credit carries a high-interest price tag, whereas the tribal peoples' crops are bought at a fraction of the market rate. Cash crops offer a further disadvantage in that they decrease the supply of available foodstuffs and increase tribal dependence on economic forces beyond their control. This transformation has meant a decline in both the tribes' security and their standard of living.

In previous generations, families might have purchased silver jewelry as a form of security; contemporary tribal people are more likely to buy minor consumer goods. Whereas jewelry could serve as collateral in critical emergencies, current purchases simply increase indebtedness. In areas where gathering forest products is remunerative, merchants exchange their products for tribal labor. Indebtedness is so extensive that although such transactions are illegal, traders sometimes "sell" their debtors to other merchants, much like indentured servants.

In some instances, tribes have managed to hold their own in contacts with outsiders. Some Chenchus, a hunting and gathering tribe of the central hill regions of Andhra Pradesh, have continued to specialize in collecting forest products for sale. Caste Hindus living among them rent land from the Chenchus and pay a portion of the harvest. The Chenchus themselves have responded unenthusiastically to government efforts to induce them to take up farming. Their relationship to nontribal people has been one of symbiosis, although there were indications in the early 1980s that other groups were beginning to compete with the Chenchus in gathering forest products. A large paper mill was cutting bamboo in their territory in a manner that did not allow regeneration, and two groups had begun to collect for sale the same products the Chenchus sell. Dalits settled among them with the help of the Chenchus and learned agriculture from them. The nomadic Banjara herders who graze their cattle in the forest also have been allotted land there. The Chenchus have a certain advantage in dealing with caste Hindus; because of their long association with Hindu hermits and their refusal to eat beef, they are considered an unpolluted caste. Other tribes, particularly in South India, have cultural practices that are offensive to Hindus and, when they are assimilated, are often considered Dalits.

The final blow for some tribes has come when nontribals, through political jockeying, have managed to gain legal tribal status, that is, to be listed as a Scheduled Tribe. The Gonds of Andhra Pradesh effectively lost their only advantage in trying to protect their lands when the Banjaras, a group that had been settling in Gond territory, were classified as a Scheduled Tribe in 1977. Their newly acquired tribal status made the Banjaras eligible to acquire Gond land "legally" and to compete with Gonds for reserved political seats, places in education institutions, and other benefits. Because the Banjaras are not scheduled in neighboring Maharashtra, there has been an influx of Banjara emigrants from that state into Andhra Pradesh in search of better opportunities.

Tribes in the Himalayan foothills have not been as hard-pressed by the intrusions of nontribals. Historically, their political status was always distinct from the rest of India. Until the British colonial period, there was little effective control by any of the empires centered in peninsular India; the region was populated by autonomous feuding tribes. The British, in efforts to protect the sensitive northeast frontier, followed a policy dubbed the "Inner Line"; nontribal people were allowed into the areas only with special permission. Postindependence governments have continued the policy, protecting the Himalayan tribes as part of the strategy to secure the border with China (see Principal Regions, ch. 2).

This policy has generally saved the northern tribes from the kind of exploitation that those elsewhere in South Asia have suffered. In Arunachal Pradesh (formerly part of the North-East Frontier Agency), for example, tribal members control commerce and most lower-level administrative posts. Government construction projects in the region have provided tribes with a significant source of cash--both for setting up businesses and for providing paying customers. Some tribes have made rapid progress through the education system. Instruction was begun in Assamese but was eventually changed to Hindi; by the early 1980s, English was taught at most levels. Both education and the increase in ready cash from government spending have permitted tribal people a significant measure of social mobility. The role of early missionaries in providing education was also crucial in Assam.

Government policies on forest reserves have affected tribal peoples profoundly. Wherever the state has chosen to exploit forests, it has seriously undermined the tribes' way of life. Government efforts to reserve forests have precipitated armed (if futile) resistance on the part of the tribal peoples involved. Intensive exploitation of forests has often meant allowing outsiders to cut large areas of trees (while the original tribal inhabitants were restricted from cutting), and ultimately replacing mixed forests capable of sustaining tribal life with single-product plantations. Where forests are reserved, nontribals have proved far more sophisticated than their forest counterparts at bribing the necessary local officials to secure effective (if extralegal) use of forestlands. The system of bribing local officials charged with enforcing the reserves is so well established that the rates of bribery are reasonably fixed (by the number of plows a farmer uses or the amount of grain harvested). Tribal people often end up doing unpaid work for Hindus simply because a caste Hindu, who has paid the requisite bribe, can at least ensure a tribal member that he or she will not be evicted from forestlands. The final irony, notes von Fürer-Haimendorf, is that the swidden cultivation many tribes practiced had maintained South Asia's forests, whereas the intensive cultivating and commercial interests that replaced the tribal way of life have destroyed the forests (see Forestry, ch. 7).